Art as an Investment: The Story of the Times-Sotheby Index

“Art was recognized as the best investment; over the past 30 years, art pieces have proven to be more profitable than most stocks.” These words were spoken by Peter Wilson, a Sotheby’s executive, during his appearance on the BBC program Money in 1966. At that time, Wilson had already transformed the outdated image of the art trade during his eight years at Sotheby’s. His innovative pre-sale marketing methods, the celebrities he invited, and the stylish social events surrounding the auctions turned Sotheby’s sales into major news events, further solidifying the outdated image of his rival, Christie’s.

After World War II, Wilson expertly capitalized on the post-war wave of prosperity, aiming to bring newly wealthy individuals into the fold. He was determined to convince businessmen and bankers that art collecting was not an exclusive privilege of long-established and cultured dynasties such as the Rothschilds, Rockefellers, or Mellons. Most importantly, he was focused on embedding the idea that art could be an investment. What he needed was to package this idea in a convincing and straightforward manner.

Wilson, managing the Goldschmidt sale at Sotheby’s, 15 October 1958. To make the auction more exciting, Wilson limited the sale to seven star lots. Guests included Kirk Douglas, Somerset Maugham, and Lady Churchill. The rising prices paid for Impressionist paintings in the 1950s had made headlines and attracted new buyers to the field.

A year after Wilson’s appearance on television, a 27-year-old Geraldine Keen (now known as Geraldine Norman) received a letter. Having studied at Oxford University and UCLA, Keen was working for The Times in London, but had recently left the newspaper to join the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. The letter from the urban editor of The Times offered her the opportunity to head a new page in collaboration with Sotheby’s auction house.

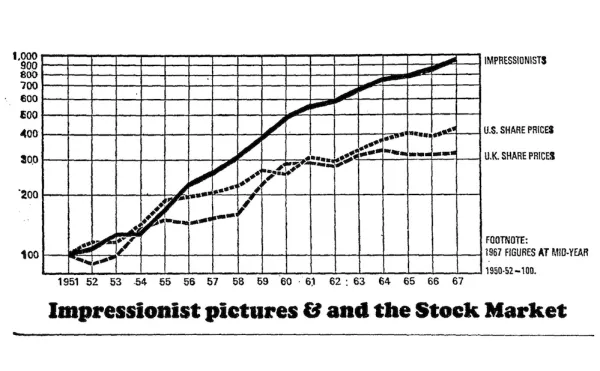

Today, many active individuals in the art world have never heard of the Times-Sotheby Index. Those who have, are likely veteran art dealers or retired auction house staff. Between 1967 and 1971, the Times-Sotheby Index was regularly published in The Times, claiming to analyze the changing prices of artworks sold at auction. Articles focusing on specific movements or sections, such as Impressionism, English silver, and Chinese porcelain, were published alongside graphs showing the sale prices from the 1950s up to the present day.

Since the 1960s, the contemporary art market has expanded exponentially. Today, it’s common to discuss an artist’s “resale value” or “collector base” in fine detail. Countless works of art are stored away in freeports, heavily guarded, where their owners avoid customs duties. The press is filled with news of record-breaking sales, endless articles about the top-selling artists, and lists of the world’s most expensive works of art. Companies like Artnet, Collectrium, Artprice, and ArtRank sell their data and forecasts on sales and trends. Speculation has become the rule. However, in 1967, the Times-Sotheby Index’s bold and radical approach to analyzing the monetary value of art, with few exceptions, was unprecedented.

Art as an Investment: The Story of the Times-Sotheby’s Index

In his 1984 article Art and Money, Robert Hughes wrote, “Our culture has been trained to view works of art as an investment.” “Today’s art market did not appear overnight; […] I believe its seeds were sown with the interesting initiative called the Times/Sotheby Art Index.” Hughes continued:

Perhaps the credibility of the Index stemmed from the graphics. These extremely biased and brief articles, with their accompanying charts, gave them the reassuring appearance of an economic page from The Times. They turned the concept of investing in art, which had seemed risky, into something tangible and realistic. They created the impression that owning art was a perfectly rational and sensible thing to do.

However, the idea of art as an investment was not without historical precedent. Émile Zola, in his 1886 novel The Masterpiece, depicted the speculative nature of the 19th-century art market. One of the characters, Naudet, a Parisian art dealer, deals with “wealthy enthusiasts” who buy paintings “just like they buy stocks on the stock market.” Naudet’s sales pitch to his clients goes as follows:

“Look, here’s an offer for you; I’ll sell you this painting for 5000 francs, and if you decide you don’t want it, I’ll buy it back for 6000 francs in twelve months.”

Naudet wastes no time and sells eight to ten paintings by the same artist in this manner over the next year. Vanity and hopes for profit intertwine, prices rise, and paintings are continuously traded. So much so that when Naudet revisits his naïve client a year later, instead of selling back the painting the client bought, he buys a new one for 8000 francs. This drives prices even higher, and the artwork becomes something like a gold mine on the hills of Montmartre, where a handful of bankers promote it amidst a never-ending money war.

In Rogues’ Gallery, Philip Hook also vividly depicts the 19th-century art market. The book includes a section dedicated to the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who introduced Impressionists to the public.

Geraldine Keen’s headlines on The Times were quite clear: In June 1968, she wrote, “Your money is safe in art.” “Fine art is a tradable asset, and it will retain its value in the international market.” The Index sparked reactions from readers, critics, and art professionals, many of whom wrote letters to the newspaper. In October 1968, one of these reader letters was published: “The Times-Sotheby Index… represents the height of vulgarity and commercialism,” wrote L.J. Olivier from Essex. “Please, God, let this wind turn. Let the ventilated vaults of the tasteless businessmen open, and let the people inside be seized, while your wretched journalists are stoned to death with fake Etruscan bronzes.”

However, the downfall of the Index came when its creator, Keen, became determined to shine a light on auction house reserves. In the summer of 1970, Keen told Peter Wilson, the director of Sotheby’s, and Peter Chance, the director of Christie’s, that she was writing a critical article about the practice of concealing unsold works purchased by the company. She had noticed that fictitious names were regularly published in sales lists distributed to subscribers (some of these were pseudonyms for buyers wishing to remain anonymous). However, this practice would later become widely known. Fiona Ford, a former press officer at Sotheby’s, explained this to Peter Hook, the author of Rogue Gallery:

“After each auction, we would go behind the curtain to learn which issues Peter Wilson wanted us to lie about.”

Keen, who had passionately supported art’s position as an investment tool, now used her expertise to push for transparency in the market. It was no surprise that her investigations were not well received by Wilson and Chance. On July 16, 1970, The Times published Keen’s article titled “Confidentiality in London Auction Houses.” Eight months later, the newspaper discontinued the Times-Sotheby Index.

Keen’s article exposed the use of false names and revealed the auction houses’ justifications for such secrecy. According to auction houses, if bidders knew the reserve price of a piece, they would be less likely to offer a bid above it. The perception that works purchased by the company were unwanted could make it more difficult to resell these works. Yet, such secrecy contradicted the very spirit of auctions. “Auction houses have greatly benefited from the public and transparent nature of their transactions,” Keen wrote. “Secrecy regarding unsold works is, therefore, contradictory.” Following increased scrutiny, auction houses corrected their practices. By 1975, both companies had abandoned the practice of including privately acquired lots in their sales lists.

By 1971, the findings of the Times-Sotheby Index had been sold to numerous publications outside the country, including The New York Times, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Connaissance des Arts. Two years later, collectors Robert and Ethel Scull sold their contemporary art collection at Sotheby’s New York branch for an eye-popping profit.

Robert Scull, a master of self-promotion, enthusiastically highlighted the vast difference between the prices they had originally paid for the works and the prices they fetched at auction. One piece, Dissolution (1958), which they had purchased directly from Robert Rauschenberg for $900, sold at auction for $85,000. This extraordinary rise in prices inspired the common method of buying new works and waiting for their value to increase. Although the Scull auction is often remembered as a pivotal moment that reinforced this mindset, the true catalyst was the ruthless logic behind the Times-Sotheby Index analyses. As Geraldine Keen herself put it:

“Picasso went up by 3 points, Renoir dropped by 2… At the time, I hadn’t realized that these had a direct effect on the art market. The Index had changed people’s opinions and ways of thinking, but it took a few years for it to really take hold. I only realized how much influence the Index had on art buyers after ten years.”